12 Proven Principles For A Really Healthy Diet

Too much nutrition information runs the risk of explaining nothing. The promise of a perfect diet for everyone is wrong. It’s time to reset our dietary choices. Let’s relearn about human nutrition from indigenous cultures and the best that science can teach us.

| | Reading Time: 8 minutes

Nutrition experts debate what diet is right for us. You read a few studies and discover conflicting information. Does scientific evidence confuse or help us understand food choices?

Internet health gurus promote their version of what’s the optimal human diet in order to sell services and products. Should you believe these “experts” when there is obvious conflict of interest?

Your best friend, a yoga teacher and animal rights activist, is excited about a new vegan protein powder and fermented raw food diet. Does someone’s idea about the perfect diet risk being incorrect even if their intention is good?

What if someone knew interesting information about health and nutrition but hadn’t studied science or medicine, would you listen? What if that person looked healthy, lean and strong, but didn’t actually know nutrition at all? Who should you follow?

We’re overwhelmed with nutritional information and about an optimal diet for all humans. Is there one diet that rules them all? Could it be more straightforward than it seems? Or is it more complicated?

For personal food choices or dietary rules, what principles guide you? Common sense counts. However, I believe there’s more to it than Michael Pollan’s entreaty in The Omnivore’s Dilemma to “eat as low down the food chain as possible.” Pollan is right because we’d all be healthier by going lower on the evolutionary food chain: eating cleaner, simple. However, there’s a lot more to a healthy diet than eating more of the good stuff, and none of the bad foods

According to The Future of Health & Wellness in Food Retailing, people believe that food choices determine health status, and effects how the shop at the grocery store. That makes perfect sense and is supported by scientific research. Because more people are focusing on wellness and disease prevention, I argue that we need a set of principles, not fixed rules, based on what actually works to promote health, and less on opinion, trends, and depending on food retailing or online health marketeering.

Let’s start with the latest research. Along the way, I’ll share observations from my fieldwork among traditional indigenous people over the last forty-five years, and back it up with my thirty-five years of clinical experience in functional medicine.No Epidemic of Modern Chronic Diseases

Since the modern diet is well-known as the cause of the obesity and chronic disease epidemic, it makes sense that researchers should look to our ancestral past for clues about the link between health and diet.

A 2018 paper on hunter-gathers informs us that the source of modern chronic diseases is civilization. Fieldwork among small-scale traditional societies in Africa and South America found multiple commonalities associated with health, activity, energy expenditure, and diet.

This study (Pontzer, Wood, & Raichlen, 2018) found that hunter-gatherers have excellent metabolic and cardiovascular health. My ethnomedical fieldwork among indigenous peoples in the Arctic, Amazon, and Andes taught me that native people living close to their ancestral diets have no obesity, no diabetes, no cardiovascular disease, and cancer is rare.Traditional Indigenous People Live Long

Researchers found that most indigenous people—if they don’t have an accident or get an infection—live as long as modern people. (Gurven & Kaplan, 2007) In traditional societies, old age is delayed. People remain robust and active, contributing to the tribe, into their 60s and even 70s.

I saw 45-65-year-old men among the Siberian Yupik compete as good or better hunters than 25-year-old men. I’ve seen 85-year old natives more active than their modern age-matched peers. I witnessed several elders who were documented by anthropologists to be over 100 years. These experiences changed my view of aging.Traditional Indigenous People Walk A Lot And Carry Heavy Things

Researchers found that hunter-gatherer men log a daily average of 14 km on foot. (Leonard & Robertson, 1997) That’s an astounding 17,500 steps. According to The Calculator Site, there are 1,250 steps in one kilometer. For Fitbit advocates—I’m one of them—that’s world-class walking. In comparison, the average adult in the U.S. walks less than 3 miles a day. That’s 4.8 km or 6,299 steps.

Indigenous people carry heavy loads, babies, crops from the fields, game from a hunt, and lift rocks to clear fields. Modern people walk on flat surfaces, like a treadmill or around the park, and carry nothing. We rarely lift anything, except if we practice resistance training at the gym, often not using heavy weights.

I expect to walk a lot when I go into the field. When I lived among the Siberian Yupik on St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea, it was not unusual to set out on foot for a trek of more than 75 miles. Among the Q’ero in the Peruvian Andes, we cover move than 20 miles across extraordinarily rough terrain at altitudes between 12,000 -14,500 feet. We set out walking, carrying full packs, before sun up and arrive at the village or next camp before sun down.

In the upper Amazon during the rainy season when the rivers fill and much of the forest becomes inundated, canoes replace walking. Canoeing or kayaking does for the upper body what carrying does for the lower body.Greater Dietary Diversity

There are few universals in what indigenous peoples worldwide eat. This alone might inform modern people that there is no one diet for everyone. Dietary composition varies depending on where indigenous people live. For example, in the Arctic where I lived among the Siberian Yupik of St. Lawrence Island in the Bering Sea, their diet consisted mostly of fat and protein, with little fiber and no simple carbohydrates. Primary food sources were walrus and seal, followed by fish, seabirds and their eggs. I ate only what they ate and was healthy, gained muscle, and felt great.

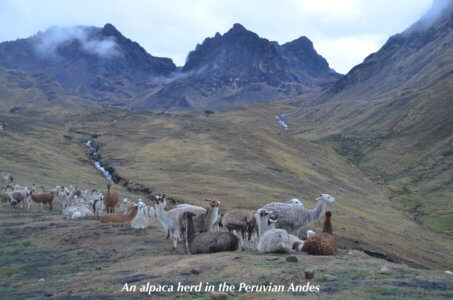

In the Andes, I lived among the Quechua-speaking Q’ero. Their diet is mostly complex carbohydrates, followed by protein from lean meat. They have no vegetable oil and eat no refined carbs. Food sources are native potato species and other tubers, some heritage corn, and grasses like quinoa, and lean alpaca meat. Diversity comes from wild berries, herbs, roots, trout from the streams, and occasional game.

Advanced cultures with ancient histories also tend to have highly diverse diets. The traditional Chinese and Mediterranean diets are examples of healthy ways of eating that have endured thousands of years. A traditional Chinese diet includes herbs like ginseng, astragalus, and lychee berries. They consume a variety of fermented foods made from soy and other legumes, cabbages, and roots. Many types of seaweed and fungi are eaten.

By contrast, the modern diet provides more food more calories, but from processed foods with lower nutritional value. Grocery stores provide less diversity amidst a myriad of choices. Whole Foods Market and other health food groceries offer more diverse choices including different types of tofu, miso, and fermented vegetables. For non-vegetarians, protein consume muscle meats without the bone. Fish are filleted. Unlike traditional cultures, modern Americans rarely eat organ meats like heart or liver. In the U.S., we don’t eat steamed whole fish with head and fins. But traditional Chinese prefer their fish prepared that way. Diversity ensures balanced nutrition over time.Macronutrient Ratios Matter But Differ Among Native Groups

Scientists calculate the amount of energy contained in foods in calories, which come from three sources called macronutrients: fat, protein, and carbohydrates. Macronutrient ratios vary from culture to culture, and according to types of diets. For example, the ketogenic diet gets most energy from fats and oils. The Paleo diet gets energy from protein and some fats.

The Yupik, and other Arctic native peoples naturally consume a ketogenic diet. American natives of the great plains ate a Paleogenic diet of high protein from buffalo and antelope. Native Quechua people of the Andes eat a high complex carbohydrate diet.

| TYPE OF DIET | % PROTEIN | % CARBOHYDRATES | % FATS |

| Modern Diet | 12 | 46 | 42 |

| Yupik | 46 | <10 | 45 |

| Tsimane | 20 | 64 | 16 |

| Quechua | 10 | 70 | 20 |

| Mediterranean | 18 | 50 | 29 |

| Ketogenic | 15 | <5 | >80 |

| Paleo | 20-40 | 1 | 40-60 |

| Zone | 30 | 40 | 30 |

Hunter-Gatherer People Eat High Fiber Foods

The Hadza in Tanzania eat predominantly a plant-based diet with loads of wild honey, consume up to 150 grams of fiber daily, and ingest lots of natural pre and probiotics.

The Tsimane of the Bolivian lowlands eat mainly high fiber tuberous carbohydrates like cassava and plantains, that are also rich prebiotics. (Kraft et al., 2018) Like other indigenous cultures living close to their traditional lifestyle, the Tsimane have almost no cardiovascular disease.(Kaplan et al., 2017)Traditional People Eat Cooked Food

An important nutritional truth is that all indigenous groups cook most, if not all, of their food. Though, diversity is the rule, cooked food is the norm. The traditional Chinese diet is composed of cooked foods. Most Chinese go their entire life without eating a salad.

In my fieldwork among the Yupik and Q’ero, and with more than a dozen other indigenous tribal cultures, it’s uncommon to see them eating raw foods except fruit in the tropical regions, and occasional raw seafood in the Arctic.

For older people and others with weakened digestion, I recommend cooked foods. Raw foods tend to produce gas and bloating because they ferment, much like a compost heap, in the gut. However, for those who can tolerate salads and other raw foods, I allow for a 50/50 diet of equal parts raw and cooked foods.

Is There An Optimal Diet?

New research by nutrition experts confirms my belief based on more than forty years of fieldwork among traditional indigenous tribes that there is no single diet that is best for everyone all of the time.

A 2017 study found both the Paleolithic and Mediterranean Diets reduced the risk for all chronic diseases associated with modern lifestyle. (Whalen et al., 2017) And, the Ketogenic diet is more effective than cutting calories on changing body shape and losing weight. (Ting, Dugré, Allan, & Lindblad, 2018)

However, after more than forty years of combined research and clinical practice, I haven’t come up with a “one-size-fits-all” optimal diet. Though this article introduces the health benefits of ancestral diets, I’m not advocating a Hazda high-honey diet or a Yupik ketogenic diet. There’s nothing easy about a traditional indigenous lifestyle. It’s a very tough life. If you lived with them for some time, few modern people would want to trade places or diet with them.

However, I’ve learned several things from my fieldwork, as well as studying the research, and also from my healthy, long-lived patients. I’ve found that principles, based on authentic indigenous ways of life and unbiased science, serve as guidepost that help make better nutritional choices.

Here’s my list of dietary principles, none of which you don’t already know.The 12 Principles of a Healthy Diet:

- Vary your diet to increase nutrient diversity.

- Eat fresh food, locally grown according to the season.

- Consume more fiber.

- Eat organically grown crops and grass-fed meat.

- Choose wild, sustainably caught fish.

- Know the macronutrient composition of your diet. Are you mainly Paleo or Keto? Mediterranean? Vegan? Vary your composition based on your health and fitness needs.

- Adjust your diet according to your activity level, health goals, and as you age.

- Avoid harmful foods. Bad foods harm you more than good foods benefit your health.

- Don’t eat too much, or too little. Eat want you need according to work and activity level.

- Eat at regular times.

- Practice intermittent fasting if approved by your doctor.

- Eat what works for you. Use trial and error like our ancestors did to come up with the optimal diet for you.

What guides your nutritional choices? Is it based on principles, or do you blindly follow a trend or fad? Even the latest science can be biased, or influenced by funding to favor the food or pharmaceutical industry. However, these plenty of good nutritional science. And there’s newer research into food choices according to your genetics. The goal is to create a personalized healthy, nutritionally effective diet based on a foundation of what’s worked for humans over time. Use modern tools like gene profiling. And, walk more. Lift heavy at the gym. And, carry heavier loads.